The Rescue of the Passengers of the S/S Danmark

Article from The Press - Tuesday Morning, April 23, 1889 - Transcribed by Mike Nelson, Aug. 2005

Tuesday Morning, April 23, 1889

SAFE ON SHORE. The Rescued Passengers of the Danmark Through Their Peril.

---------------

LANDED FROM THE MISSOURI.

---------------

A Warm Welcome for the Ship and Her Brave Captain.

---------------

THE STORY OF THE ESCAPE.

Speeding Forward to the "Promised Land" with no More Food. The Broken Shaft and the Fear That All Would Go Down - The Glad Sight of the Missouri - Transferring the Seven Hundred and More Souls from the Doomed Vessel."The Press," with Its Special Tug, the First to Greet Them.

The steamer Missouri which rescued in mid-ocean the 735 passengers and crew from the disabled and sinking steamship Danmark, came to her dock in this city at 6 o'clock last night, having on board 365 of the rescued passengers. The other passengers had been loaded on the Azores Islands. The Missouri arrived at the Delaware Breakwater at 1 o'clock Monday morning, as reported in THE PRESS yesterday, and anchored for the night. At sunrise she proceeded up the river with flying colors, the heroic Captain Murrell receiving salutes from every passing vessel.

He was welcomed first by THE PRESS special tug Startle over seventy-five miles down the bay, and PRESS reporters were the first Philadelphians to grasp his hand and congratulate him on his magnificent exploit. Five hours afterward, when near the city, he was welcomed by prominent officials and citizens, which met him in tugs and kindly allowed the representatives of other newspapers to accompany them. Then he was welcomed by enthusiastic thousands at the dock when the ship came to anchor.

The story of the rescue of the Danmark people by the Missouri and of the subsequent voyage to the haven at the Azores, and thence to Philadelphia, makes one of the most marvelous marine recitals of the decade. The small army of passengers and seamen were transferred in a raging tempest from the sinking Danmark to the staunch Missouri without a single mishap. They were safely landed at the Azores an hour and a half after the last mouthful of food had been eaten. Not only did the captain safely land the 735 passengers, but while they were on his ship their number was added to, a birth having taken place the night of the rescue.

The only death that has occurred since Captain Murrell had anything to do with the Danmark's passengers - that of a child occurred after he had safely landed them in Philadelphia.

Below, without collaboration and in detail is given the narrative as gathered by PRESS reporters.

THE STORY OF THE VOYAGE Putting to Sea in Good Weather and Meeting with Mishaps.

The Danmark began her ill-fated voyage on March 20, when she left Copenhagen. The Thingvalla Line, to which she belongs, has made special efforts to secure a large number of emigrants, and several hundred peasants boarded her there. She went thence to Christiana, and after stopping at Christiansand was ready for sea on March 24. She then had a crew of 59 and 665 passengers, of whom all were in the steerage but 26, who were cabin passengers. The Danmark put to sea in good weather, and Captain Knudsen was hopeful of making a quick and easy passage. He was anxious to do so because the Danmark was the first ship of which he was master and this was his second rip in her as captain. Although but 35 years of age, Captain Knudsen has been for many years in the service o the Thingvalla Line as first mate.

Almost immediately after putting to sea, March 24, the Danmark began to experience the bad luck that followed her to the bottom of the ocean. The wind blew from the West, right in her teeth, and retarded her passage. Cross seas swept the decks of the massive 2600-ton steamship again and again, and the Danmark labored heavily. The more than 600 passengers from Denmark and Sweden [and Norway] confined between decks experienced much discomfort. It was a picturesque party of seekers after new homes in the Promised Land, and yet possibly not unlike scores that cross the ocean each year by the Thingvalla Line. All Scandinavia was represented and there were a very large number of women and children. Many of the women were young and unmarried and were on their way to America either to meet sweethearts and marry or to seek places in families as domestics. A very large number of the steerage passengers were bound to homes in the West, principally in Iowa, Nebraska and Wisconsin.

It is claimed by the officers that the Danmark behaved very handsomely in this wild weather and she had advanced almost midway of her journey by April 4. She was then in about longitude 46.16 North and latitude 38.36 West. The gale had increased in violence and the weather was threatening and hazy. All of that day, which was Monday, the Danmark rode the long, heavy swells, which were almost mountainous in their rolling. Many of the passengers were sick, and those who were not were scarcely venturesome enough to trust their legs to the deck.

The Shaft Had Snapped.

The afternoon was wearing away and Captain Knudsen was on the bridge. It was about 3.50 o'clock, as near as can be gathered, when a violent shock shook the huge fabric of the Danish steamship from stem to stern. To some it sounded as though a powerful explosion had taken place in her hold. To others it seemed that the ship had been suddenly dropped by the waves that were toying with her on a ledge of rocks and allowed to remain there stationary.

Loud cries rang through steerage and cabin. Some shouted "The ship is lost." Meantime the captain and his officers, with faces that showed their concern, made an examination below, when they went forward and held a long and serious consultation. The passengers demanded to know what had happened. "Do not be alarmed," they were told. "We hope it is not serious."

But it was serious. What had happened was this: While plunging down the steep declivity of a wave which left her propeller, revolving lightning-like, entirely in the air; the shaft of the Danmark had snapped as neatly in two as a school boy's slate pencil. It had snapped close to the stern port, and the portion leading to the engine, when it broke, had smashed down into the bottom of the ship with such violence that at first it seemed as if the whole after part of the hull had been started. The shaft was about fourteen inches in diameter, and the force with which the broken end had inflicted the blow below had (to use the words of Purser C. A. Hemper) "practically split her stern open."

Vain thoughts of repairing the broken shaft were soon abandoned, and the officers were called to face a much more serious question. The blow of the shaft had caused the Danmark to spring a leak. The engines were kept going and the pumps were started, while the vessel was kept head to wind as much as possible. An examination resulted in the conclusion being reached that the injury to the hull of the Danmark was not serious, at least for the time being. Still the great ship, with her enormous human freight, was practically helpless in that angry sea. She could make no headway, and all that was left for her to do was to wait for help.

A more thorough search was made of the engine room some time later by Captain Knudsen. It was reported that Engineer Kass was missing. Down in the engine room, doubled up and bleeding, the Captain found the engineer. He was quite dead. His skull had been apparently crushed into a pulp by a blow from a piece of the machinery that was operating the pumps.

Captain Knudsen ran on deck with a face that was fairly gray with alarm and concern and told the news. The body was removed and the information speedily spread about the ship. It had anything but a reassuring effect on the now thoroughly alarmed passengers. Mutterings could be heard on every side, as is the case in every crowded steamship in time of an accident.

"I understand," one passenger was heard to say, "that the machinery was known to be imperfect when we left Copenhagen."

"The chief engineer has been found dead," said another, "but does anyone know what killed him?"

At the Pumps All Night

So the gossip of the steerage ran for hours, and the passengers, who did not know what would happen next in this unfortunate voyage, were doing a great deal of grumbling. The pumps worked all Monday night incessantly, and succeeded in keeping the water down. The Danmark, without her power of locomotion, rolled and tumbled in the sea very much as a log does in a Schuylkill freshet. There was no sleep on board the ship, and on Tuesday the outlook was even gloomier than on the day before. The wind still blew from the West, the sea was rough, the ship was unmanageable, the passengers were in despair and the Captain stalked the bridge incessantly, sweeping the sea line with his glasses.

Some sisters of a Scandinavian religious sect in New York went about among the terrified passengers calming their fears, giving them religious counsel and endeavoring to cheer them up. Their efforts had a very marked effect, particularly among the women. A Swedish preacher, on his way to the West, held religious services during the forenoon, or attempted to hold them, for between keeping his Bible on the table before him and keeping himself from tumbling into the corner, he was sorely troubled to keep the thread of his discourse.

But finally about 1.20 in the afternoon the succor that Captain Knudsen had been so anxiously scanning the horizon for appeared within the stormy ----- of his vision in the shape of the steamship Missouri, of the Atlantic Transit Line, Captain Hamilton Murrell.

HELP FROM THE MISSSOURI. - Cheering the Approach of Their Deliverer. Rescuing All Hands.

Signals of distress were flying when the Missouri came into view. The passengers saw her almost as soon as did the officers of the Danmark. A great cheer went up from the heartsick emigrants. They saw in Captain Murrell their deliverer.

Just here a word should be said about who Captain Murrell, probably the most talked-about man this morning, is. He is young for a steamship master even now, as he is but 29 [years of] age, yet he has been a captain in the merchant marine since he was 22. He comes from a family that has been a seafaring one for generations. He himself has followed the sea since he was 8 years old. He successively commanded the Maine, the Surrey and the Missouri, and has always run to Philadelphia and Baltimore. He had cargo for both these ports when he fell in with the Danmark. Captain Murrell is a handsome man, stout and florid, with a pleasing face and a nerve like that which has made naval heroes famous.

When he saw the signals of distress flying from the masthead of the Danmark he at once ran to her assistance. He set the commercial code of signals to work and asked what was wanted. The answer [came] promptly from Captain Knudsen that he would like to have his passengers taken on board the Missouri. How many passengers had the Danmark? queried the signals. Nearly 700 came the answer. Captain Murrell gave a bewildered and meditative whistle. He knew his vessel was stout and staunch, having been built only last September, but he also knew that his tonnage was much less than that of the Danmark, and besides he had neither the quarters nor the provisions for so many people.

He quickly answered back, "We can't take your passengers unless it is absolutely necessary, but we will in the meantime give you a tow if that will answer for the present." Captain Knudsen answered that that would do, and arrangements were made to take the Danmark in tow.

Battling with Raging Seas.

This was a much more difficult task than appears to a landsman when told about it. The seas were very rough and the wind was blowing with savage intensity. After two hours' hard work, during which oil was used with much success, to calm the angry waves, a tow rope was got on board the Danmark. Three points were open to the rescued and rescuer. St. John, N. F., was about 700 miles distant: Halifax was 1150, and St. Michael's, in the Azores, was 720. It was decided to attempt to reach St. John's. At 4 o'clock that afternoon the Missouri turned the head of the helpless Danmark to the sea and started on a North-westerly course. The wind was still a gale coming in a steady volume from the West and Northwest It was a hard night for both ships, the seas were very heavy and the Missouri had all she could do to hold on to the disabled vessel. When the storm increased in violence at midnight the Danmark tugged so heavily astern that a wire bridle of the towing line was carried away, the forward bits and the windlass end were bent. The tow rope still held, however, but the Danmark, as was constantly feared, did not go adrift.

At daylight the wind and sea had somewhat moderated. Still Captain Murrell found that he had made practically no headway to the Westward during all the toiling of the night. He also detected signs of ice to the windward, and he indicated to Captain Knudsen that he would change his course and try to take the Danmark to the Azores. This was assented to, and at 6:30 A.M. of April 6 he squared away for far off St. Michael's, making a speed of about seven knots an hour.

Things had not been going well with the Danmark all this time. It was found that the water had gained during the night. The laboring of the ship had assisted the work begun by the broken shaft, and the water was pouring into the after hold faster than the pumps could spout it out. Captain Knudsen summoned all hands to work, and threw seventy tons of cargo overboard and the pumping continued.

An hour after the Captain of the Thingvalla liner had assented to changing the course from St. John's to the Azores, he signaled Captain Murrell again.

"We are leaking considerably," the signal ominously said, "and we have three feet of water in the hole."

"Well, what shall I do?" signaled back the commander of the Missouri.

"Keep on towing," was the answer. Captain Murrell did so but not for long.

A few minutes after this exchange of signals, what Captain Knudsen had dreaded and contended against, became apparent. The second engineer, who had taken the place of dead Engineer Kaas, came wearily on deck and approached the Captain.

"It's no use," he said dejectedly, "I can't keep the pumps going."

"Why can't you?" asked the captain, petulantly.

"The water has put the fire out, and we can get no steam. We're done."

"How much water is in the afterhold now?" said the Captain.

"Four feet."

"And it is gaining how fast?"

"It is gaining like the tide."

Captain Knudsen buried his face in his hands. "There is no help for it, I suppose," he said.

"None whatever. She is going down and nothing can save her."

A consultation of the officers and able seamen was hastily called in the cabin. A council of war was never more grave. The case was fairly stated by the Captain, who asked the engineer to repeat to him what he had just said. This was done in a few words. While the steerage passengers wandered about and the cabin passengers speculated on what was going on, it was determined to desert the ship at once. The storm made it almost as dangerous undertaking as remaining on the ship that they could already almost feel slowly settling beneath their feet.

Abandoning the Ship

So it was in pursuance of this decision that this signal a few minutes later was dashed to the Missouri:

"Must abandon ship. Water gaining rapidly."

Quickly the towing rope was cut and the Missouri dropped astern of the Danmark and waited for further word, which Captain Knudsen said he would send.

First Officer Gleahn, of the Danmark, soon came in a boat. He was worn out and downhearted.

"Our vessel is sinking," said he to Captain Murrell. "We can't keep her afloat much longer, and my captain deems it prudent to leave her if you will take her passengers and crew."

"I'll do it," promptly answered Captain Murrell. "It will be a hard job to make the transfer, but we can do it. We need all the provisions you have and we must leave here just as soon as we can."

First Officer Gleahn bowed gravely and with the military dignity that marks the officers in the German marine service at all times and under all circumstances descended the ladder and went back to the Danmark to assist in the work of leaving the ship.

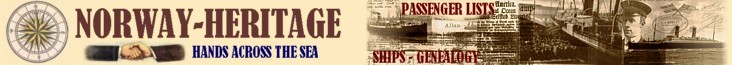

LEAVING THE DOOMED SHIP - How the Transfer Was Effected - Women and Children First

To the eye of the observer from the deck of the Missouri the Danmark had very perceptibly settled in the water at the stern. The passengers could be seen huddling toward the bow in mute terror, as if to get as far as possible away from the waves that were constantly washing over the after part of the ship.

But what had happened to the Danmark to make the leak increase so rapidly? Simply this: The broken end of the propeller shaft had dropped from the stern, carried away by the weight of the propeller, leaving a hole as big as an ordinary man's body, through which the water poured into the hold of the ship like a mill ----. To add to the danger, the straining of the night before had weakened the compartments farther forward, and they, too, were being rapidly filled. No pumping could have availed against that tremendous rush of water, even had it been possible to operate then times the number of now useless pumps the Danmark possessed.

It was necessary that prompt action should be taken. Captain Murrells action was as prompt as that of Captain Knudsen. "I decided," said he, speaking of it yesterday, "that we would have to take these people off just as soon as we could, and more than one of us felt sure that the racked and pounded Danmark could not keep afloat in the sea until everybody was transferred."

Two lifeboats were at once lowered away. One was in charge of Second Officer Forsyth and the other of Third Officer Lucas.

"Go to that ship," said the captain on the Missouri, "and bring only the women and children first. Then may God help us to get them aboard, with this ugly sea hammering our sides."

By this time it was 11 o'clock. The wind was blowing harder than ever. The waves were breaking now and then over both ships with a force that sent the spray half masthead high. To undertake the transfer of nearly 800 people in such a sea seemed like courting certain and wholesale death. Nothing but a lifeboat could live in such sea, and nothing but the best of seamanship could prevent those boats from being dashed to pieces against the iron sides of the ships should they approach them. Still it was do or die, and the two lifeboats of the Missouri pulled away toward the Danmark with strong arms impelled by willing hearts.

On the heavily rolling and steadily settling Danmark the bustle and preparation for departure had some time since begun. Nervous men began to gather their belongings. Hysterical women sobbed as they looked after their little ones. Fair-haired Swedish children, with pale, waxen faces and terrified blue eyes, clung to the dresses of mothers and the coats of fathers with mute agony of fear.

"All baggage must be left behind," sung out the captain. "We can only permit each person to take a small bundle of things that they absolutely need."

Using the Bowlines.

This order struck deeper despair to many a heart than had been inflicted by the terrors of the situation. It meant in cases too numerous to mention the loss of the little "all" of these seekers after a new home in a strange land. Still the order was obeyed and the people prepared to embark.

"Women and babies first," shouted Captain Knudsen, as the boats of the Missouri lay under the side to receive the first load of helpless emigrants. Women and babies first, it as, but were ever women and babies handled in such a way before. The volume of the billows made the use of ladders out of the question. The boats could not approach near enough. So the method of bowlines had to be adopted. The average reader does not know what a bowline is or how it is used. In landing a person from a vessel with a bowline he is put in a sort of a frame and swung far out as with a derrick and then slowly and safely lowered. This is the method used during the trying rescue of the Danmark's passengers. Keeping the boats clear the emigrants were safely placed in them while they rose and fell on the waves. First three or four women would be swung out and then some of the little ones would be sent to join them. The small children would be put in a basket and lowered into the boat. Then they would be taken out and the basket would be swung back to the boat again for more small occupants.

An amusing scene occurred in the midst of this work. A very little girl was about to be put in the basket. The little girl was very badly frightened, but she suddenly remembered something and breaking away from her father ran and rolled and tottered into the steerage. In a few minutes she returned clasping a big doll to her bosom as tightly as dolly was ever pressed before, and the little girl and the doll both went over the side of the Danmark in a basket, and were safely drawn in a basket over the side of the Missouri.

The work of getting the people on board the Missouri was as difficult as that of taking them of the Danmark. Nine men were required to pull on the bowline. Sixty-five children and nearly 200 women were moved first, and then came the turn of the men. The two Missouri boats were assisted by seven boats from the Danmark, and they kept constantly plying back and forth in their dangerous work. Second Officer Forsyth says that at one time the waves were so high that all the other boats were concealed from view. Just after the men had begun to disembark three loud pistol shots were heard in the steerage of the sinking vessel. A passenger who had with him three magnificent Danish hounds had shot them before leaving the doomed ship sooner than see them drown.

Captain Murrell gave orders to the master of each boat that it would be necessary for them to bring each trip a quantity of provisions from the Danmark, well knowing that the provisions of the Missouri would not last a day with such a crowd as his ship was about to receive. According, each time a boat emptied its human freight on to the deck of the Missouri it also emptied a big store of biscuit, flour, butter and fresh meat. It was well that Captain Murrell thought of this, for had he not the condition of the rescued passengers after a day on his vessel would not have been much better than it was on the Danmark.

While the work of transferring the passengers went on, Captain Murrel kept his eye anxiously on the sky. The weather looked dirtier than ever. The wind began to blow from the Southwest and a falling barometer warned him that there might be more trouble ahead.

It was 4 o'clock. All the passengers had been transferred and were crowding all parts of the Missouri. The captain and his officers still lingered on the Danmark as though loth [sic] to leave her. Captain Murrell sent word to Captain Knudsen to come on board. The summons was obeyed, and with tears in his eyes Captain Knudsen was the last to leave his vessel. He was the last to go on board the Missouri, and, warmly clasping Captain Murrell's hand, congratulated him on what he had done. He had succeeded in transferring in the midst of a howling storm from one vessel to another 665 passengers and a crew of sixty-nine without an accident of any kind and all in five hours and a half.

The Danmark Lost to View

Just as Captain Knudsen came on board the Missouri the fog came down and shut the Danmark from view. Captain Murrell went over the provisions with Captain Knudsen before deciding what course to pursue. He found that he had barely provisions for three days and deemed it best to make all possible speed for the most convenient port. Although St. Johns was the nearest as to distance, he knew that it would be hard to make that place in the face of the storm. He also knew that St. Michael's was not much farther away and that he could reach it easily.

"The Azores it is," said he, as he gave the order to lay the course at 5.30 o'clock.

Just then the fog lifted and disclosed a last view of the Danmark. She seemed to be going down. Her stern was awash with the water and four feet of her prow was above the surface.

Captain Knudsen looked at her a minute and turned away with tears in his eyes.

"OVERBOARD WITH CARGO" - How Brave Captain Murrell Performed His Duty to Humanity.

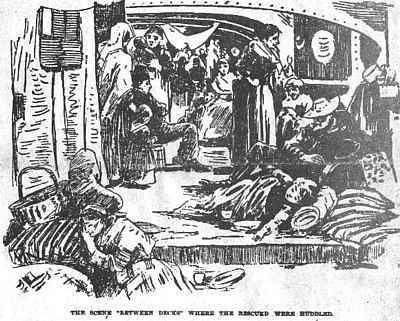

Then every soul thrilled with new hope turned to look about the broad decks of the ship which had saved them from being lost at sea. But as broad and long as the Missouri's decks were she found herself crowded by the rescued 700 from bow to stern. How was she to carry them, shelter them and protect them were three queries running through every seaman's mind, but gallant Captain Murrell sent an order ringing the ship's length, "Overboard with the cargo."

The return cargo of the cattle vessel was large rags and baled stuff, and it quickly went drifting out in the ocean, back toward the abandoned hulk of the Danmark

The next order was "unbend the sails for shelter." These sails were used to cover up the hatches on the cattle-sheltered deck and to cover in the alleyways. Mattresses were placed under the bridge and sails and awnings were used as beds in the coal bins, hatches, alleys, and every other conceivable space.

The officers and engineers of the Missouri gave up their rooms to women and children and the cabin was given to the Danmark's first-class passengers. Captain Murrell, with the captain of the Danmark, slept in the chartroom, and in the wheelhouse, 10 x 8 feet, were put eleven unmarried women. It blew very hard on the evening of the rescue and the wind and sea increased all night.

A Child of the Storm.

At 1 o'clock on the next morning the ship's physician was aroused from his nap by an urgent call to the first officer's room. Then, at 1.20 o'clock, as though there were not enough passengers already on board, young Mrs. Linne, one of the women saved, gave birth to a daughter. The news spread through the ship even at that hour, and seemed to have a cheering effect on everybody. The chief officer, in whose room she was born, paid his respects to the mother early the next morning and christened the baby Atlantic Missouri Linne.

"The next day was Sunday and," narrates Captain Murrell, "I shall never forget the utter desolation and bedragglement these poor creatures presented." Twice during that day some Scandinavian sisters who were among the rescued and who were bound for New York, held religious services down among the emigrants. All the passengers participated reverently.

But a new and greater peril had been staring the officers of the Missouri in the face. The captain had taken account of provisions and had found that with the most frugal living there were only enough to last three days. This with the Western Islands hundreds of miles away. That Sunday at midnight such a terrible wind came from the sea that the vessel's commanding officer deemed it, in view of the number of lives on board, unsafe to make further progress and the vessel was hove to for six hours. This delay, in the face of the rapidly failing supplies, brought new anxieties to the officers, while the passengers were happily ignorant. They must have foreseen the danger to some extent, however, for three days the fare of all on board was bread, butter, cheese and water. The water supply would not have lasted but for the ship's lucky possession of large condensers, used in preparing the water for its cargoes of cattle.

The Glad Cry "Land, Ho!"

The Missouri's engines were being strained so that when it came that the young captain must say to the hundreds on board "there is nothing left for you to eat," he could at least give them encouragement by telling them to prepare for the sight of land. A dramatic climax was reached on Wednesday, April 10. At 8 o'clock on that morning the last scanty supply on board the ship was served and devoured eagerly. Not a sail had been sighted. Captain Murrell, while they were devouring it down in the hatches, hungry and worn with care and anxiety himself, might have been seen gloomily pacing the bridge, when the lookout broke his reveries with the glad cry of "Land Ho' Sir."

Far off in the horizon where the sunlight ---- the sea was vaguely outlined the promised land of the Azores - the beautiful Western Islands. Captain Murrell swept the distant coast with his glass, and in a few moments the joyful news was on every tongue. Even the picturesque little Danes in caps and boots and quaint frocks lisped it. At 9.30 o'clock on that morning the spyglasses were no longer needed, for the Missouri was steaming into the big bay that leads to the harbor of St. Michael.

The Azores, occupied by the Portuguese, were revealed to the poor Norwegians and Swedes, stranger islands of more brilliant tropical beauty than they had ever dreamed. The heavy swell of the ocean had gone and they were delighted to find themselves riding on the bay of silvery ripples beyond which stretched landscape full of lazy beauty.

The Missouri anchored off St. Michael's, and while the passengers occupied themselves watching the dark-skinned natives and catching glimpses of hooded cloaked women on shore captain Murrell sought the Danish consul and inform him of the rescue at sea and the state of things. The Danish consul showed much gratitude and was anxious that the captain should take as many of the passengers on to America as possible.

After a further consultation with the British consul it was decided to continue the voyage with 365, including all the women and children and the men related to them, the remaining 385, mostly men, were sent ashore in boats with the understanding that their consul would provide for them until further arrangements could be made. In the meanwhile the steward of the vessel, by order of the captain, cleaned the island out of provisions. Great firkins of butter, a ton of biscuit, live sheep, calves, chickens and flour were brought and stored on board.

The Trip Homeward

On April 11 the vessel had finished coaling at 6 P. M. and sailed at 6.30. She made a Southern passage to get fair weather and got it and succeeded in making 260 miles a day. All the officials on the abandoned Danmark who had shared Captain Murrell's fears in the voyage to the Azores were left on the island, but the purser, doctor, butler, two cooks, baker, stewardess and one waiter who continued the voyage to America. During the homeward voyage on last Saturday at 7.30 A. M., in latitude 36.25 North and longitude 68.30 West, the lookout sighted an abandoned schooner with masts and bowsprits standing. The captain sent the chief officer to her in a boat to burn her, as he considered her dangerous to navigation. When the officer and crew reached her, all they could make of her name was "Mary ----, Bethel, Del." She was found to be too thoroughly soaked with salt water to burn. On the evening of the same day, at 6.30, the vessel sighted a boat of 300 tons, wrecked and lying on her side. Both of these wrecks excited the greatest interest among the passengers, who talked of them and wondered whether the people on them had been saved as they were, and the steward passing through the hatches that night heard them praying for all people in peril at sea. The second wreck might have been that of the missing pilot boat Turley, from which no word has come.

The rescued 365 spent all last Sunday, as the voyage was ending, in worship and prayer. They were aided in their devotions by the peaceful-faced sisters and preachers who had risen among them since their peril. That evening, their last to see the sun sink in the sea, a sound of great harmony and beauty went out from the ship Missouri far across the water. The children of Denmark were singing hymns. While they sang the glad news was flashing at last over cable and land wires that every soul on the lost steamer Danmark had been saved. At 9 o'clock on Sunday night a great black hulk came out of the dark with flaming eyes, a beacon for the wary pilot crafts. Out from cover twenty miles from the coast, near Five Fathom Light, shot the Delaware pilot-boat Henry Cope, with her flash lights gleaming through the darkness, until answered and at 10 o'clock Pilot Chambers, leaning from his skiff, grabbed a gangway of rope and, scaling the black hull of the Missouri, stepped upon the decks.

"THE PRESS" SPECIAL TUG - Getting on Board the Vessel Ahead of All Others - Scenes Coming Up

Great excitement and interest attended the fulfillment of THE PRESS Prophecy by the cablegram on Sunday evening that the Missouri had rescued all the Danmark's passenger and might be expected to arrive here with 365 of them at any time.

Up to midnight dispatches from the Breakwater gave no news of her, and THE PRESS decided to put men on board of her as soon after she was signaled as possible. The only way to accomplish this was by a special tug.

By 1 o'clock yesterday morning Captain Hughes, in his night cap, and from his second-story window, had chartered the big tug Startle to THE PRESS, for service at the Breakwater until she put reporters on board the Missouri, and she was in readiness for immediate service. Then came the early morning dispatch announcing the arrival of the ship at the Breakwater, which made THE PRESS more determined than ever to get the first Philadelphia newspaper men on her decks.

Just as the first light of dawn was coloring the East yesterday morning THE PRESS reporters and a staff artist passed between long lines of bright cars on Delaware Avenue to South Street dock and jumped aboard the Startle where she lay impatiently snorting and fussing with her ropes, with Captain Patrick Byrnes already in the pilot-house. The captain said it would be a great day, and rang a gong that in tug language means "good-bye." The Startle, with a puff of triumph, plunged out into the river and was soon tearing ambitiously around the bend off Gloucester, with the sun and Philadelphia boats in her wake.

Greeted with Enthusiasm.

Everything she overtook or met on the river bade her good morning with their shrill blasts, and Captain Byrnes, who, from the start, exhibited emotional enthusiasm over THE PRESS men's right to board the Missouri, first kept anxiously sweeping the water with his spy-glass. Quarantine, Chester, Wilmington, Pensgrove, and all the beautiful shore scenes glided by, but still no sign of the ship the country was anxious to hear from. So the captain went through his breakfast in a remarkably dyspeptic way and rushing back to the pilot house ringing the gong to go faster. When Fort Delaware loomed up at 8 o'clock with no sign of her yet the captain said he would find that boat if he had to go outside the capes, and, rushing over to Delaware City, took in a ton and a half more of coal in ten minutes and then steamed off into the bay. An hour and a half more passed and the captain began thumping his spyglass back in its case, as it showed him nothing but a fleet of oyster boats that circled the bay where the horizon met it ten miles away.

At 10 o'clock the Captain was just telescoping his glass for the hundredth time, when a little black speck crossed it and caught his eye.

"You gentlemen ready," he asked, "to get on the Missouri."

"Certainly, why?" was the eager chorus.

"Oh nothing, just got my eye on something down there seventeen miles."

Ten minutes later the glass was leveled again and in a moment he dropped it and said: "You gentlemen better be ready to get on the Missouri, 'cause that's her." The boat in the distance looked the size of a skiff. But in a remarkably short time she was the size of a tug, then of an excursion steamer and then she became tremendous with her black hull, three towering masts and red stack. The spyglass showed crowds of people on her decks and the spray at her bow.

"The Press" Men on Board.

But Captain Byrnes waited to see the "white of her eyes," and then he gave his whistle four short jerks. Immediately a curl of steam leaped from the steamer's whistle and the captain said "It's all right gentlemen," and rang the gong to stop. The Missouri, now 500 yards away, had also lowered her speed and the Startle swung round and started up the river with her, approaching nearer her side. A great handsome fellow with gold braid appeared on the bridge, and the tug Captain, as though suddenly electrified, leaned out of his pilot window and cheered. Somehow THE PRESS men took it up and an answering cheer ran along the entire deck of the steamship.

Then there was a scene of wild enthusiasm above which thundered the voice of Captain Byrnes, "Get that gang plank over there." There were 10 feet between the tug and the steamer, and they lashed the water down between to foam as they pushed along side by side. The narrow gang plank was extended from the upper deck of the tug to the upper deck of the ship and it tumbled and made zigzags as THE PRESS men crept over it. As soon as their foot touched the deck the handsome fellow with gold braid came half-way down the steps to the bridge with hands extended.

"Captain Murrell," exclaimed one of the three. "THE PRESS offers its congratulations first."

"Welcome, gentlemen, on board the Missouri," was the hearty reply.

That was the way THE PRESS boarded the Missouri and bade good-bye to the Startle off Cross Ledge Light at 11 o'clock and eighty miles from the city.

The Run Homeward.

The trip from there to Philadelphia was crowded with incidents, arousing the utmost enthusiasm. On the decks and down in the hatchways of the vessel could still be seen how the rescued passengers of the Danmark lived during their voyage to the Azores and from St. Michael's harbor here. Most of them were in a pitiable state having lost all their luggage and having what little they possessed on their backs. Noticeably first were the Danes, Swedes and Norwegians in their picturesque outfits and high-legged boots, striding the decks and drawing comfort from their short, black pipes.

But the scene of scenes on the Missouri was between decks down in the hatchways and alleys, the cattle stalls and coal bins, where 200 women and little children had been bunked for days. The sails and awnings and blankets and shawls, the latter gotten for them at the Islands, were spread on the floor, and they lay and sat upon them in all conditions and positions. Some of the girls were making their toilet preparatory to coming into port, and others were promenading the alleys. All were smiling with delight over the end of the trip. At dinner time every emigrant was provided with an earthen bowl and cup, and the steward's men went the rounds with pots of soup, boiled meat, potatoes, thick slices of bread and big firkins of butter from which each was plentifully helped.

A wee, golden-haired Danish girl lay asleep on her blanket in a coal bin, with a knife and fork crossed on her breast, dreaming of Denmark, while the green shores of Delaware and New Jersey glided by. While the steamer was coming up the river Captain Murrell received two testimonials. The first from the emigrants saying:

"We, the undersigned passengers of the S. S. Danmark do hereby express our thanks to you for taking us from that sinking steamer and for the kind and humane treatment you have shown us."

The other was from the cabin passengers and read:

"It is for us a great pleasure to express our heartfelt thanks to you and your officers and crew not only because you rescued us all in your ship, but for the kindness and courtesy shown us."

The Prediction of "The Press."

Captain Murrell was delighted when he learned THE PRESS had predicted that the Missouri saved the Danmark's people. "You hit it exactly right, too," he said, on the way we were coming here and the speed we were making.

A great crowd of Danes got hold of a copy by THE PRESS, and one of them, who spoke English, translated yesterdays reports of the vessel's movements.

A tugboat conveying two Custom-house officials, Captain Isaac N. Simon and J. Rax Bricking, reached the steamer early in the day and they boarded her.

When the steamer was off Delaware City yesterday afternoon she hoisted her signal and then up went the American and English flags. After that the excitement began in earnest. The City of Chester passing sent cheer after cheer as a greeting. Between Chester and Philadelphia the tug New Castle, bearing Cadwalader Biddle and a number of Philadelphia newspaper men, and the Quarantine tug Visitor, bearing Port Physician Randle and a number of newspaper men arrived alongside. The newspaper men learning THE PRESS had sent a special tug to the steamer first begged the use of the police tug Stokley, which was granted, but the Stokley had only got out a few miles when she broke down. Then the newspaper men begged passage in the tugs Visitor and New Castle.

From Wilmington up boat after boat passed the steamer and drew alongside to cheer Captain Murrell and his officers. There was a continual din of shrieking whistles and even from the farm houses and country seats along the shore handkerchiefs were waved. An officer of the boat was continually on the bridge to answer salutes, and the pilot's "steady!" and the helmsman's "aye! aye! sir!" were drowned in the clamor of great joy.

AFTER THE ARRIVAL - Scenes at the Wharf - Captain Murrell's Modest Little Speech

The news that the rescuing vessel was coming up the river and would reach her dock at the foot of Washington Avenue during the afternoon, brought hundreds of people flocking to the wharves. They began to gather shortly after dinner, and before 3 o'clock all the wharves below pier 51 were black with men, women and children. At pier 48, where the Missouri was to dock, an officer stood on guard at the wicket gate and permitted none but authorized persons to enter. Even there, however, a crowd soon gathered, and grouping about the river end of the pier, waited patiently for the Missouri's arrival. During the afternoon John H. Campbell, surveyor of the port; Dr. Andrews, the police surgeon, and many well-known business and shipping men joined the party at the pier.

Shortly after 2 o'clock considerable excitement was aroused by the sight of a large ocean steamer coming up the river. The cry went from wharf to wharf that the Missouri was coming, and the customs inspectors and longshoremen made a rush for the piers. When, however, the inbound vessel came close enough to be identified as the British King, there was a general feeling of disappointment, which, curiously enough, found vent in a spontaneous cheer for the big passenger steamship.

John Rath, the general passenger agent of the Thingvalla line, had come over from New York before noon, and, accompanied by J. H. Anderson, passenger agent for Peter Wright & Sons, and P. F. Young, manager of the American Transportation Line, which runs the Missouri, had gone down the river on the tug New Castle to meet the incoming vessel. Agent Rath had come over with plenty of money and a determination to do everything possible for the rescued passengers, and preparations on a liberal scale were made to receive them. F. H. Myers, the Pennsylvania Railroad's dock agent, took charge of the arrangements for receiving the Danmark's passengers, and with the assistance of J. Paul Bacci, the dock superintendent, had a great table, over a hundred feet long, out under the dock shed, and set out with wholesome, palatable food.

It was after 5 o'clock and the crowds upon the wharves had begun to get weary of waiting in the chill wind when a sight of the great red smokestack of the Missouri was caught rounding the bend in the river above Gloucester. The crowd as not anxious to be deceived again and kept discreetly silent until doubt of her identity was no longer possible. She came up slowly, flanked on either side by a small flotilla of tugs, and as she approached Reed Street and the wharves above there was a fluttering of hats and handkerchiefs on her crowded deck and from the shore a great spontaneous cheer went up. Then the whistles of the tugs and steamboats on the river and the locomotives on the Pennsylvania tracks commenced lustily to blow, and for a few moments the din was deafening.

Swinging into the Pier.

It was 5.25 when the Missouri with her crowded decks of handkerchief-waving people came opposite the Washington Avenue pier. The New Castle was on the West and the Tench Coxe on the East and with the assistance of these puffing tugs she was turned around. It required ten minutes more to get her up to the end of the pier, where, without taking time to run her into the slip she was moored and a ladder dropped down. As the vessel came close the people on the wharf clapped their hands and cheered, and Captain Murrell, of the Missouri, who was standing on the bridge directing the movements of his vessel, was given an ovation. He bowed, and then, as the ladder dropped, several of those who had gone down in tugs to meet the vessel early in the morning scrambled down to the pier.

Orders were given to admit none but newspaper representatives and other authorized persons to board the vessel, but fully fifty clambered up the ladder. Among them were a number of business men and a messenger from a florist, bearing a large and handsome floral ship, set in a sea of smilax. It was the gift of J. B. M. Showell, E. B. Shoell, L. A. Flanagan, C. W. Davis and Mrs. G. W. Elkins to Captain Murrell as a tribute to his heroism, grit and kindness. The Captain was caught on the deck, modestly endeavoring to escape from the crowd. No formal presentation was made. The floral design was simply passed over to him without ceremony, and he accepted it in a two-minute speech of thanks. He said:

"I thank you for my officers and crew, as well as for myself, for this expression of your good will toward us. I am sure that your courtesy is meant as well as for them as for me. It is said that there are no English sailors left, but this voyage has convinced me that the British sailor still lives. I express the feelings of the officers and crew of the Missouri when I say that we are glad that we have been able to bring these people safe to port. We have only one case of illness, that of a child, who is so far recovered that I think the port physician will be able to give us a clean bill of health. What I did was only what any other man would have done, and what I would do again under the circumstances. I thank you or my officers and crew for this kind welcome on our arrival in Philadelphia."

Captain Murrell's brief address was applauded not only by the visitors on the boat but also by many of the Scandinavian passengers taken from the Danmark, who could not understand his language but appreciated the scene nevertheless. The Captain then made another attempt to escape. He was cornered and informed that President Brockie, of the Maritime Exchange, wished to convey to him an invitation to accept a reception in the rotunda of the Exchange building, at Walnut and Dock Streets, at 12 o'clock to-day. The Captain deprecated the movement to lionize him, but finally consented, and then came an invitation from the Society of the Sons of St. George to attend as a guest the annual dinner at St. George's Hall to-night.

TAKING OFF THE PASSENGERS.

In the meantime arrangements had been making to take off the rescued passengers A steep gangplank was laid down and the line started. As fast as they set foot upon the pier they were hurried to the table under the long shed and served to a standing lunch.

Notwithstanding the many weary days they had spent upon the ocean, the Danmark's unfortunate passengers seemed loath to leave the Missouri's decks. They crowded around Captain Murrell, clasped him by the hand, patted him on the back, and more than one buxom, yellow-haired Swedish maiden threatened an oscillatory attack. To satisfy them, the Captain passed along the line, shook hands with all he could reach, and then, as he finally escaped toward his cabin, the expression, in the Scandinavian tongue, "God Bless you, Captain, and good-bye," came welling up from a hundred throats.

Among the early visitors to the Missouri was Rev. C. W. Holm, the pastor of the Swedish Assembly of Brethren, on North Broad Street. He gathered the passengers about him, talked to them reassuringly in their native tongue and assisted materially in getting them disembarked without confusion. Among the last of the rescued people to leave the Missouri were the Danmark's surgeon, Dr. Gilbert Gesperson, Purser Hember, Baker Lundquist, and William Schanderberg, a young lad, who was second steward on the wrecked vessel. They all spoke with the greatest feeling of their kind treatment by Captain Murrell and his crew.

Captain Murrell was taken in tow by an old stevedore friend, C. W. Davis, and at half-past 7 took a train in Camden for the latter's home in Riverton, N. J., where he spent the night.

Dr. Gesperson and the members of the Danmark's crew brought to Philadelphia went to New York last night. About forty of the rescued passengers who are bound for points East, were also put in cars at the foot of Washington Avenue about 9 o'clock and sent to New York. The others, who were bound West, were put on a special train at midnight and started for Chicago.

Agent Rath gave instructions that every attention should be paid them, and they will all be taken care of until they reach their destinations.

A dispatch was received from Washington late in the afternoon stating that Secretary Windom had authorized the commissioners of emigration at Philadelphia to use the "emigrant fund" in meeting all proper expenses incurred in providing for the shipwrecked passengers.

It is estimated that the Danmark was worth $250,000 and her cargo is valued at $50,000.

Death of a Child on Shore.

Shortly after the passengers had been landed the six months' old infant of Samuel and Marie Nielson, a young couple from Copenhagen, which had been ill during the voyage, died in its mothers arms. The child and its parents, together with several other passengers who were ailing or who had no particular destination, had been taken in charge by the Commissioner of Immigration and lodged with Mrs. A. L. Kaney, at No. 22 Christian Street. There the child died from the results of exposure.

The others who were taken to Mrs. Kaney's were Christian Ferdinand, Steve Ferdinand, Fanny Sanders, Julius Jensen and Christian Linnee and her infant born on the Missouri.

The old emigrants were kept at Castle Garden until shortly before 1 o'clock this morning, when they were put upon Pennsylvania Railroad trains which had been brought down to the foot of Washington Avenue. About 310 were taken West, and will reach Chicago on Wednesday morning. The others were taken to New York. Those who are at Mrs. Kaney's will be cared for by the Commissioner of Immigration.

Notes of the Voyage.

"If ever there was a noble man who did a noble deed," said Chief Engineer Arthur N. Cross, "it is Captain Murrell." Second Mate Forsyth, who is the man who discovered the disabled steamer, echoed this sentiment.

Captain Murrell speaks in the highest terms of his officers and crew for the assistance given him in rescuing the Danmark's passengers. He modestly says the praise belongs to them. During the transfer of the passengers from ship to ship Second Officer Forsyth was struck in the mouth by the prow of a boat that was suddenly raised by the waves and had all his front teeth knocked out.

Purser C. A. Hemper, of the Danmark, who accompanied the Missouri to Philadelphia, says that to the crew of the rescuing vessel the people on the Danish ship owe their lives.

Among those on the Missouri who were coming to Philadelphia were Mr. Laringe and wife, Edward Simon and Thomas Thomas.

WHO WILL PAY THE LOSS? - An Interesting Legal Question Over the "Jettison" by the Missouri

An interesting legal question has arisen from the casting overboard, or jettisoning, as it is called, of a part of the Missouri's cargo in order to rescue the passengers of the Danmark. Who shall have to bear the loss? Such an emergency as this has not yet been provided for in the code of international laws. There is no universally accepted principle upon which to base a decision in the matter.

In questions of loss at sea, where only a part of the cargo is affected, the general usage is to distribute the loss among the consignees of the cargo and the owners of the vessel. This is in accordance with the law of General Averages. Henry R. Edmunds, a lawyer conversant with the legal relations of vessel owners and consignees, said yesterday, relative to this matter: "the general rule where a portion of the cargo has been cast overboard for the purpose of saving the vessel and the balance of the cargo is that the ship and the portion saved must pay for that which has been thrown overboard. But this is not the case with the Missouri. This is a case where the goods were not jettisoned to save the ship or her passengers, but to save the passengers of another ship. There is no doubt but that the lost ship, or her cargo, if the vessel had kept afloat, would have to bear the burden of any losses that incurred in saving her. As it is the Missouri will have to stand the loss. A decision has been rendered in similar case, I think, by a Massachusetts court, which, if sustained as sound, will invalidate any claim of the Missouri."

"That vessel will have a claim on the baggage of the rescued passengers to make up for her jettisoned cargo, but I fancy this will not bring her much return. But I believe the owners of the Danmark are to some extent liable for the Missouri's losses. They entered into a contract with the passengers of the vessel to bring them to New York, and in this they failed. Here is an opening by which the owners of the Missouri may in some degree reimburse themselves."

Mr. Edmunds, however, thought that no such measure as this would be resorted to, but that all the losses sustained by the jettison would be assumed by the insurance companies, although they were not liable. But the loss on cargo not insured would have to be borne by the owners of the Missouri, who might recompense themselves as best they could.

King Christian and the Danmark

COPENHAGEN, April 22. - On receiving news of the rescue of the Danmark's passengers King Christian drove to the residence of the wife of the Danmark's doctor to inform her of her husband's safety.