By Børge Solem - 2025

The Transition from Sailing Ships to Steamships

Before the rise of steam-powered transatlantic travel, most emigrants crossed the Atlantic on sailing ships, a journey that often took between six and twelve weeks, depending on weather conditions and the departure point. The quality of the crew and the ship also played a significant role in determining the duration and safety of the journey. On average, the crossing by sail from Norway to America between 1840 and 1874 took 53 days. Between 1840 and 1850, the sailing time from Ireland to America ranged from 42 to 84 days.

Conditions onboard sailing ships could be extremely harsh, often marked by overcrowding, poor ventilation, scarce food supplies, and a high risk of disease outbreaks. Many passengers endured malnutrition, severe seasickness, and relentless exposure to the elements during these long and perilous voyages.

The introduction of steamships revolutionized emigrant transport. By the mid-19th century, steam-powered vessels significantly shortened the crossing to 6 to 9 days, reducing both the physical strain and health risks for emigrants. Steamships provided more reliable schedules, better food provisions, and improved living conditions. The Allan Line, as a leading steamship operator, played a major role in making transatlantic migration safer, faster, and more accessible.

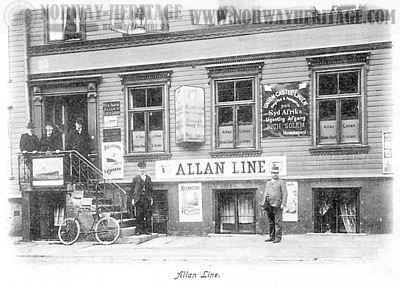

Many emigrants chose to travel via Canada, taking advantage of the Allan Line's well-established steamship services. The Allan Line was founded in 1854 as the "Montreal Ocean Steamship Company". This company offered a reliable and affordable passage from Great Britain to North America, attracting emigrants bound for both Canada and the United States.

The Allan Steamship Company and Its Role in Emigration

The Allan Line maintained a fleet of steamers departing from Liverpool twice a week. These steamships offered a cost-effective and efficient way to cross the Atlantic. The route was favored for its safety and convenience, as passengers spent minimal time on the open ocean before reaching the calmer waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River. In addition to departing from Liverpool, the Allan Line also operated sailings from Glasgow.

The Allan Line steamers also called at Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, and alternated with Moville, Ireland, to embark Irish emigrants. Moville was frequently used as an embarkation point for emigrants from Northern Ireland, especially those traveling from Londonderry (Derry). Many emigrants traveled by small boats or trains from Londonderry to Moville, where transatlantic steamers could pick them up more efficiently, avoiding the shallow waters of the River Foyle.

Government Regulations and Emigration Contracts

By the late 19th century, most European governments had introduced laws regulating emigration, aimed at protecting emigrants from fraud, exploitation, and unsafe travel conditions. National regulations often required licensed emigration agents to follow strict guidelines when arranging passage. These agents had to issue standardized contracts that clearly outlined the terms of the journey, including transportation routes, provisions, accommodation, and medical assistance.

Governments also mandated inspection of emigrant ships, ensuring they met safety and hygiene standards. Authorities in countries such as Britain, Germany, and Scandinavia imposed rules to prevent overcrowding and required shipowners to provide sufficient food and medical care. Canadian and U.S. immigration officials worked closely with European governments to ensure that only healthy and financially stable emigrants were admitted into their countries.

Securing Passage and the Emigrant's Journey

The Allan Line encouraged emigrants to secure their passage before leaving home by purchasing tickets from an authorized Emigration Agent. These agents, based in cities across Europe, sold through-tickets that covered the entire journey from the emigrant’s home to their final destination in North America. Agents were also available in America, allowing settlers to purchase prepaid tickets for friends and family back home. The ticket often included:

- Travel from various locations in Northern and Eastern Europe to England, often via train and steamship services.

- Railway transport across England, typically from east coast ports to Liverpool or Glasgow.

- Accommodation in a boarding house while waiting for departure in Liverpool or Glasgow.

- Transatlantic passage on an Allan Line steamship.

- Rail or steamboat transport within Canada and the United States to the emigrant’s final settlement destination.

- Provisions provided during the voyage.

Arrival in England and Departure from Liverpool

For many emigrants from Scandinavia, Germany, Eastern Europe, and other regions, the journey to North America began with travel to England. They typically traveled on smaller steamers from ports such as Hamburg, Bremen, Rotterdam, and various Scandinavian cities to England. From there, they were transported by rail across the country, usually from east coast ports like Hull, Grimsby, or Harwich to Liverpool. One of the largest companies offering feeder services to England was the Wilson Line of Hull. Hull served as a major hub for transmigrants.

The Allan Line had representatives and agents in the English ports where emigrants arrived from Europe. These representatives guided and assisted them with accommodations, food, and the conveyance of luggage. This system streamlined travel logistics for emigrants, ensuring a smooth transition between different modes of transport and minimizing potential delays and confusion upon arrival.

Upon arriving in Liverpool, emigrants often faced several days of waiting before their scheduled departure on an Allan Line steamship. Most emigrants traveling with the Allan Line stayed in emigrant boarding houses affiliated with the company. Steamship lines often made agreements with boarding masters to help organize lodging. As Britain’s largest transatlantic departure point, Liverpool had a bustling emigrant quarter where passengers could take care of last-minute travel arrangements.

The Allan Line's Liverpool operations were centered around Canada Dock and later Prince’s Dock, where emigrants boarded their ships. The company's agents assisted passengers with embarkation procedures, ensuring that those with through-tickets were properly processed and ready for departure. Once onboard, passengers settled into their designated steerage or intermediate accommodations, beginning their 6 to 9 day journey across the Atlantic.

Conditions Onboard: Life During the Atlantic Crossing

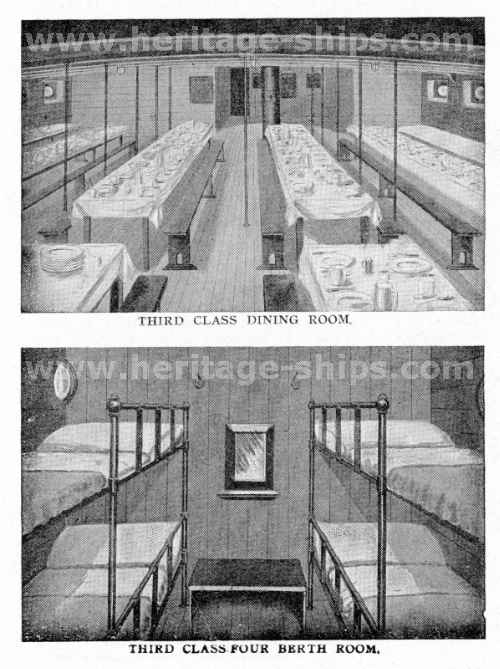

The experience of emigrants aboard Allan Line steamships varied depending on their class of passage. Most emigrants traveled in steerage, which, although an improvement over sailing ships, remained a crowded and uncomfortable experience. The largest ships of the line would often carry more than 1,000 steerage passengers. Passengers were provided with bunks or hammocks, along with bedding and basic necessities. However, space was limited, and privacy was virtually nonexistent. The sleeping quarters were divided into rooms, separated by walls made of planks or canvas, each accommodating 20-24 persons.

From the establishment of the line in 1854 until at least 1882, the sexes were separated, much to the displeasure of many married couples. Married men were separated from their wives, and boys over the age of 12 were placed either with their fathers or, if the father did not travel with the family, with other men. Families were only allowed to be together on deck from 7 a.m. until 8 p.m.

It is unclear exactly when this practice changed, but as new ships were constructed toward the turn of the century, steerage was reclassified as third class, with sleeping cabins for 4, 6, or 8 persons located on the main deck. Passengers were then divided into three sections: one for unmarried women, one for families, and one for unmarried men. Greater efforts were made to accommodate third-class passengers as comfortably as possible, both to meet competition from other lines and to respond to growing demand from passengers. Dining saloons, sitting rooms, music rooms, and smoke rooms were fitted for the exclusive use of third-class passengers.

Food rations were distributed according to a set schedule, with meals typically consisting of bread, oatmeal porridge, salted meat, potatoes, and tea. While food quality had improved compared to earlier emigrant crossings, shortages and monotony were common complaints among passengers.

To prevent the spread of disease, ship doctors conducted routine health inspections, and cleanliness was strictly enforced. Intermediate-class passengers enjoyed slightly better accommodations, with more personal space and improved dining options. The presence of stewardesses on board ensured that women and children received additional assistance and care. Despite the challenges, the speed of steamships meant that emigrants endured these conditions for only six to nine days, a significant improvement over the long and grueling voyages on sailing vessels.

Seasonal Routes: Summer and Winter Services

The Allan Line operated on a seasonal route system, adjusting its destinations based on weather conditions. During the summer months, ships primarily sailed to Quebec, allowing passengers to travel inland via the St. Lawrence River. However, during the winter months, when ice blocked the St. Lawrence, ships were rerouted to Halifax, Nova Scotia, or Saint John, New Brunswick, which remained ice-free year-round. This ensured a continuous flow of emigrants, regardless of seasonal challenges, and allowed travelers to continue their journeys by rail from these eastern ports. The Allan Line occasionally also disembarked passengers in Baltimore.

There was less demand for transport during the winter, as emigration was affected by seasonal variations.

Arrival and Processing in Canada

Upon arrival in Canada, many emigrants were taken to Grosse Île, a quarantine station in the St. Lawrence River. Here, they underwent medical inspections to prevent the spread of infectious diseases. Those suspected of illness were detained, while the rest were allowed to continue their journey. Clothing and belongings were often disinfected before passengers were permitted to land.

Once cleared, emigrants disembarked at Lévis, Quebec, an important reception center where they received further instructions for travel. The Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) maintained a station at the Allan Line docks in Lévis, allowing emigrants to transfer seamlessly from ship to train. In the picture to the left, railway lines are visible, extending all the way down to the quay area. This direct connection minimized delays and helped emigrants continue their journey quickly and efficiently. Some passengers continued to Halifax, another key port for transatlantic arrivals. Canadian authorities processed newcomers and provided guidance on employment opportunities and settlement options. They also created records, such as passenger lists, that today serve as valuable sources for genealogists and researchers.

Expansion of Rail and Competition with CPR

By the late 19th century, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) had emerged as a major competitor to the Allan Line, not only in rail transport but also in transatlantic shipping. In an effort to challenge the Allan Line’s dominance, CPR acquired the Beaver Line, establishing its own shipping routes between Britain and Canada. The Beaver Line, along with the Dominion Line, had been competitors in the Canadian trade but never came close to matching the strength of the Allan Line. This new competition provided emigrants with more options but also intensified the rivalry between the two companies. The Allan Line also sought expansion and acquired the State Line in 1891.

In terms of rail transport, the expansion of CPR's transcontinental railway, completed in 1885, made it easier for emigrants to settle in Western Canada. While the GTR remained the primary route for those heading to Ontario and the U.S., CPR provided a direct link from Quebec and Montreal to the Prairies and British Columbia.

Rail and Steamship Transport from Halifax and Saint John

For emigrants arriving in Halifax, the Intercolonial Railway (ICR) provided a direct link to Quebec and Montreal, where travelers could connect to the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) or the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) for westward travel or routes into the United States. The ICR was completed in 1876, greatly enhancing transportation options for those entering through Halifax.

Similarly, those arriving in Saint John, New Brunswick, had access to the New Brunswick Railway, which connected to the Intercolonial Railway and facilitated travel towards central Canada and the U.S. border. These rail links ensured that emigrants could continue their journey efficiently, reducing delays and improving access to settlement areas.

In addition to rail transport, many emigrants also traveled by steamboat on the Great Lakes as part of their journey westward. This was especially common for those heading to destinations in Ontario, Michigan, and the Upper Midwest of the United States. Steamboat routes connected major ports such as Toronto, Kingston, and Hamilton with American cities like Buffalo, Cleveland, and Chicago, offering an alternative or complementary mode of transportation alongside rail travel. For many emigrants, this combination of steamship and railway travel provided a flexible and cost-effective means of reaching their final destinations.

Border Crossings and U.S. Immigration Processing

Many emigrants who arrived in Canada eventually crossed into the United States, seeking opportunities in growing industrial centers. Before 1891, U.S. immigration controls at land borders were relatively lax, and emigrants could often travel freely by purchasing a train or steamboat ticket. However, after the U.S. Immigration Act of 1891, more stringent regulations were introduced, requiring health inspections and identity checks at designated entry points.

Key border crossings included:

- Rouses Point, New York (serving emigrants arriving via the Grand Trunk Railway from Quebec)

- Detroit, Michigan (a major crossing point from Windsor, Ontario)

- Niagara Falls, New York (facilitating rail and ferry connections from Ontario)

- St. Albans, Vermont (a primary entry route for emigrants heading to New England)

By the late 19th century, U.S. immigration officers stationed at these points performed medical examinations and questioned emigrants about their employment prospects, financial status, and final destination. Despite these controls, many emigrants chose to travel via Canada to avoid the congestion and stricter inspections at Ellis Island, which opened in 1892. Some Canadian immigration records were shared with U.S. authorities, streamlining the entry process for those deemed admissible.