Disaster on Lake Erie in 1852

April 2001 - By Nanna Egidius, Trond Austheim & Børge Solem

In the middle of June 1852 a group of emigrants departed from Christiania bound for Quebec on the bark Argo, mastered by Capt. Olsen. The transatlantic crossing in those days could be quite unpleasant, and quite hazardous. We can only imagine what relief the passengers on the Argo must have felt as they reached Quebec on August 12th. However, the immigrants now faced another long journey, which went by railroad and wagon, for some also partly by foot, but first and foremost by ship on the Great Lakes. The inland voyage was also combined with a considerable danger to the venerable newcomers. Captain Olsen on the Argo contracted with a company to carry the emigrants and their baggage to Milwaukee for seven dollars for each adult and half fare for the children. On August 14th the baggage was brought aboard a large steamboat and in the evening at five o'clock they departed from Quebec. At six the following morning they came to Montreal. Captain Olsen had accompanied the passengers, and took leave of them there. Shortly after he had gone, an accident occurred. Thorsten Nilsen Majestad from Valdres fell overboard as he was bringing his baggage of the boat. It was right pitiful for the others to see how he struggled. And no means were on hand whatsoever with which to save him. Arrangements were finally made for dragging, whereupon he was found, but by then he was dead. This event was all the more tragic since he had a family, which mourned its lost provider At Montreal their baggage was taken in wagons about one English mile, and then they traveled by steamboat for about twenty-four hours. they passed through many locks which they looked at with wonder. They reached Toronto but could not get a boat to proceed the day they arrived there. Their baggage was unloaded on the wharf, and most of the immigrants spent the night under open sky. At eight the next morning they left by steamboat, and in the afternoon of the same day they landed below the Niagara Falls, near the ingenious hanging bridge made of steel cables. Many of them had decided to go near this masterpiece and inspect it, but they had to forego this, as their baggage was immediately loaded on wagons and drawn by horses on a railway for about sixteen English miles. On this trip they had the opportunity to view the great and much-famed waterfalls, Niagara. They came to the town of Kingston late in the evening. There, too, their belongings were placed on the wharf, and again most of the immigrants found lodging on the wharf. Some of the immigrants left for Buffalo on a small steamboat at five o'clock the next morning. At five in the evening the boat returned and got the rest of them. From Quebec to Buffalo some seventy-five poor people from Valdres had free transportation. But here they had to remain as they did not have enough money to pay passage across the Lakes. At Buffalo a group containing of 132 Norwegian immigrants boarded the steamer Atlantic, mastered by Capt. Patty. At eight o'clock of the evening on August 12th, the Atlantic departed from Buffalo bound for Detroit. The total number of passengers was 576, comprising the 132 Norwegians, a number of Germans, and the rest Americans. About two o'clock in the morning of August 20th the Atlantic collided with the Ogdensburg, and the disaster was a fact.. The description above is mainly based on a letter from Erik Thorstad, Town of Ixonia, Jefferson County, Wisconsin, November 9th 1852, to parents and siblings in Øyer. The white line on the map below shows the route Erik Iversen Thorstad and the other Norwegian immigrants took from Quebec to Milwaukee. The white star marks where SS Atlantic sank in 1852. Below is Erik's own description of the voyage and collision.

Since it was already late in the evening and I felt very sleepy, I opened my chest, took off my coat and laid it, together with my money and my watch, in the chest. I took out my bed clothes, made me a bed on the chest, and lay down to sleep. But when it was about half past one in the morning I awoke with a heavy shock. Immediately suspecting that another boat had run into ours, I hastened up at once. Since there was great confusion and fright among the passengers, I asked several if our boat had been damaged. But I did not get any reassuring answer. I could not believe that there was any immediate danger, for the engines were still in motion. I went up to the top deck, and then I was convinced at once that the steamer must have been damaged, for may people were lowering about with the greatest haste. Many from the lowest deck got into the boat directly, and as the boat had taken in water on being lowered, it sank immediately and all were drowned. Thereupon I went down to the second deck, hoping to find means of rescue. At that very moment the water rushed into the boat and the engines stopped. Then a pitiful cry arose. I and one of my comrades had taken hold of the stairs which led from the second to the third deck, but soon there was so many hands on it that we let go, knowing that we could not thus be saved. We thereupon climbed up to the third deck, where the pilot was at the wheel. I had altogether given up hope of being saved, for the boat began to sink more and more, and the water almost reached up there. While we stood thus, much distressed, we saw several people putting out a small boat, whereupon we at once hastened to help. We succeeded in getting it well out, and I was one of the first to get into the boat. When there were as many as the boat could hold, it was fortunately pushed away from the steamer. As oars were wanting, we rowed with our hands, and several bailed water from the boat with their hats.

A ray of light, which we had seen far away when we were on the wreck and which we had taken for a lighthouse, we soon found to be a steamer hurrying to give us help. We were taken aboard directly, and then those who were on the wreck as well as those who were still paddling in the water were picked up.

This boat, which was the one that had sunk ours, was of the kind known as a propeller, driven by a screw in the stern. The misery and the cries of distress which I witnessed and heard that night are indescribable, and I shall not forget it all as long as I live. The number of drowned were more that 300, of whom sixty-eight were Norwegians. Many of the persons who were in the first class were drowned in their berths or staterooms. The Norwegians who were rescued totaled sixty-four, but most of them lost everything. I saw many on board the propeller who had on only shirts. The newspapers blame the command of the "Atlantic" for this sad event and reproach them most severely and accuse them openly of having murdered three hundred people.

The propeller soon delivered us to another steamboat which brought us to a city called Detroit, where we arrived at eight the next morning. After we had got some provisions for our journey, we continued on a steam train. Late in the evening we reached a large torn in Illinois, called Chicago, where we spent the night and had everything free. On the trip there, we saw many beautiful farms and orchards as well as many attractive buildings. We left the following morning by steamboat, and after five or six hours we reached Milwaukee. That was on the twenty-second of August. We stayed with a Norwegian where we remained until the twenty-eight of the same month. Since the city had taken up a subscription for our support, we lived free of charge, and in addition each person received eleven dollars in money. With this money I bought two coats, a pair of trousers, a pair of shoes, two shirts and a bag.

From Milwaukee I went by steam train twenty to twenty-five miles without charge, and then I footed it, reaching Østerlie's the thirtieth of August. There I have since remained. I am well and have, God be thanked, been in good health all the time. Although I have lost all my possessions, I have not lost courage. The same God who has helped me in the time of danger will, I hope, continue to be my protector."

Another account of the disaster is the one of Amund Eidsmoe. He and his wife Gjertrude, and two children were passengers on the Atlantic and survived. In the Story of His Own Life, which he wrote in July 1901, he tells about the voyage and the accident. His written account of his immigration and the collision was printed in the August 1986 issue of the Sons of Norway Viking. Robert R. Eidsmoe of Rio Verde, Arizona, the grandson of Amund forwarded an extract from his story, and have granted us permission to present the account on the site.

Part of Amund Eidsmoe's story: (I left Valders, Norway, April 5th, 1852, with my wife and two children - Ole a son by my first wife and Gunil, a daughter by my living wife.) It was fortunate for us that we had no knowledge of the danger and adversity that were to meet us on our way, otherwise we should hardly have started on the trip. Already on the second day we were met by an omen of ill-indication for a safe journey; namely, the ship that was to carry us had already gone. Before another ship came, nine weeks had passed. This made deep inroads into our stock of provisions so we had to make more purchases. It was not then as now. We went on a sail boat and had to furnish our own provisions.

We were in the company, then held a council and decided to seek an intermediary comfort in the rural district, rather than go into town. We settled in Ringerike and remained there three weeks, awaiting news of ships to sail, but in vain. So we went to Drammen and remained there five weeks with the same wish and the same desire. Eventually the hour of departure came and we could go to Christiania. We hired a sailor with a small boat to take our goods, while my wife and two children and myself went on foot to Christiania the next day - four Norwegian miles (28 English miles). There they were in the process of fitting a ship for passengers, but we had to wait still another week before it was completed. Yes, now we came into peace and had it well, I should say so: On the ship we were always in danger of falling from the heaving and plunging of the waves and in our rooms we were thrown from one wall to the other, now up and now down. It continued in this manner for eight weeks and four days until we arrived at Quebec. Here we bade farewell to the ship and its company and were loaded with our goods onto a steamboat. Up to this time we had been only Norwegians in our "traveling" company but now we had traveling comrades also of other nationalities. The boat carried us up the St. Lawrence to Montreal. As our goods were loaded onto the wharf, one of our company, Tostein Fulhja from Slindre, was drowned. From Montreal we were to travel by rail and together with Tostein's widow and little child, we were marched into the train. She was nearly overcome with grief. It was a pitiful sight to see and think about.

From our car we could see in the distance the Niagara Falls, where grandeur is beyond my power of description. So we came one evening to Buffalo. Finally, we had arrived at the land of promise -- The United States, and we poor Norwegians were full of joy when we heard that many who lived there spoke our own language. But we soon became suspicious of the honesty and trust-worthiness of these Buffalo Norwegians. As we stood on the wharf and looked about, there came to us one, who to judge by his attire, was a sailor. He spoke to us and said we were lucky to have come to this good land from the less good Norway, and he held a learned discourse as to how we should act to become prosperous, etc. His talk was affirmed by several young men who claimed that this man's words could be relied upon by us and that it would be of great value to me to note carefully all that he stated. We stood there, as in a church, clad in holiday attire, anxious to hear and remember each one of those valuable words. In this way the time passed until it became dark. Then he stopped as if in deep thought, came closer to me and said, "Come, I waht to tell you something." I followed him several steps, whereupon he stopped suddenly, grabbed me with both hands, one on each side and fumbled with my trouser pockets, which he searched in a hurry to discover whether or not I had anything in them. To his ill fortune and my Good Luck, he found nothing excepting a good pocket knife on my right side, whose sheathe was buttoned to my pocket. This he grabbed and disappeared in the crowd and we saw him no more.

A large number of people and goods of every description were now crowded together onto a large boat called the "Atlantic" and at eleven o'clock it moved off on Lake Erie. There were many people and all wanted to find a place to sleep. As many as found room went down into the cabins, but many had to prepare their beds upon the deck. I and my family were among the latter. The deck was crowded with every conceivable thing: baggage, new wagons, and much other stuff. So we lay down to rest but sleep was not of long duration. When it was near midnight we were awakened by a loud crash and saw a large beam fall down upon a Norwegian woman of our company. It crushed several bones and completely tore the head off a little baby that lay at her side. Another ship had collided with ours and knocked a large hole in the side of the "Atlantic" so that a flood of water rushed into the cabins and people came up as thick and fast as they could crowd themselves. It seemed as if even the wrath of the Almighty had a hand in the destruction. The sailors became absolutely raving and tried to get as many killed as possible. When they saw that people crowded up they struck them on the heads and shoulders to drive them down again. When this did not help, they took and raised the stairway up on end so the people fell down backwards again. Then they jerked the ladder up on the deck. All hopes were gone for those that were underneath. Water filled the rooms and life was no more.

People rushed frantically from one end of the boat to the other. The trap doors were torn open and goods and people were swept into the water. Then was the life of a person of little value. My wife and children and I were miraculously saved; although swept into the water as the ship sank, with much swimming around with my wife and children on my back, we were picked up by the other ship. When I discovered that all of my family were alive, I was full of joy, as if I had become the richest man in the world, despite the fact that we had lost all of our goods. We had lost all but our lives, but they were precious, we now realized. An account of the catastrophe's cause I have from one of our newspapers and is as follows:

The "Atlantic" sailed out from Buffalo in the evening at eleven o'clock and to sight the Propeller Ogdensburg that belonged to a competitive company. Between these there was a bitter enmity and the captain of the Atlantic became desirous of running over the Ogdensburg and sinking it. All the lights were turned out so that the act of running down the rival company's boat would be unnoticed. At the last moment the Ogdensburg had time to turn hastily aside to escape the Atlantic and advanced a short distance, but in anger at this attack, the Ogdensburg turned and with a mighty spring, pushed a big hole in the Atlantic's side so that the water soon caused the boat to sink. The loss of life is estimated at about 300, of whom 60 were Norwegians. A trial of the officers of each ship was held with the result that the Atlantic was blamed for the misfortune. Mr. Petty, the captain of the Atlantic, was arrested and taken to Milwaukee, but what happened to him later on, I do not know.

From Detroit we came by rail to Chicago, where we received lodging and food. We went from Chicago to Milwaukee by boat. We had with us people of different nationalities -Germans -Irish - I do not know what they were all called, but all had the same distinguishing marks: half naked and without baggage or effects.

When we arrived at Milwaukee, the Germans were very kind to us and had taken up contributions so we were all supplied with money and clothes. A merchant, named Carlsen, was very kind to us and gave me a suit of clothes and $30.00 in cash. There were probably those who received more, but I was glad that they had helped us this much.

We now got a man to take us over land to Springdale, Dane County, Wisconsin, with oxen. We knew there were acquaintances there from our neighborhood back home who had settled there several years before. As any one may know, it was up to us to search for work so as to get a little to live on.

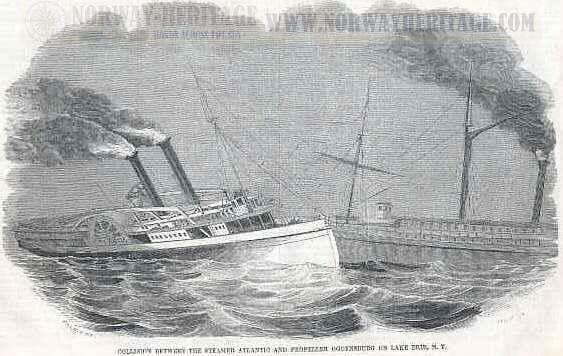

From the Gleason's Pictorial, Boston Saturday, September 11, 1852:

The scene which is presented by our artist , was a most heart-rending catastrophe. At the time of the collision a dense fog was prevailing. The passengers were all in bed, and the Atlantic was in charge of the first mate. Immediately following the collision the outmost confusion prevailed among the deck and steerage passengers, a very large portion of whom were Norwegian emigrants. Many of them, in their terror, jumped overboard instantly. Capt Petty vainly endeavored to calm their fears, by assuring them there was no danger, hoping to keep the steamer on its course, and reach port in season to save them; but the water gained so fast on the efforts of the crew, that by the time she had proceeded two miles from the spot where the collision took place, she was found to be rapidly sinking. The fires in the engine room were extinguished by the rising water, and a scene of terrible confusion followed.

The emigrants, who could not understand a word spoken to them, added horror to the scene by their cries and exhibition of frantic terror. The cabin passengers, and all others who could be made to understand the exhortations and orders of the captain and officers, remained comparatively calm, and provided themselves with chairs, settees and beds, all of whom wore patent life-preservers, which buoyed them up in the water, and they were thus saved. Great numbers of the immigrants jumped overboard in their terror, whiteout any provision for their safety, and thus rushed on to certain death. The fog was a sad hindrance to the efforts made at rescue, but some 250 were picked up by the Ogdensburg and taken to Erie.

The Ogdensburg had kept in the wake of the Atlantic, and those on board of her did all in their power to preserve the lives of the hundreds of human beings who were now seen struggling in the water. The cause of the dreadful accident is variously stated, and was, doubtless, owing to the officers of the respective vessels not readily understanding the manner in which they should have steered according to law under such circumstances.

The loss of life is ascertained to have been some two hundred! As usual, there are many affecting and interesting incidents related as having occurred. Mr. Dana, who was lost, was very efficient in saving the lives of passengers, and exhorted them to cling to the life-preservers, when in the water. When the boat went down, he took a settee and plunged overboard; but at the same moment, some twenty or thirty emigrants leaped over on to him, and he went under. The last persons taken from the boat were Mr. Givan, clerk of the boat, and Mr. Buell, first engineer. The steamer had then sunk, all but her stern, and they, with some Illinois passengers, were clinging to a rope attached to a floating mast and the wreck, being up to their shoulders in water.

As soon as the shrieks of the drowning passengers were hushed, the voice of a little boy was heard, and it was then first discovered that a child about eight years old was also clinging to a rope a short distance off. The little fellow, talking to himself, was saying: "O, I can't hold on much longer! If papa was here, he would hold me up." The man from Illinois, a fine, powerful fellow, immediately moved along the rope, and seized the boy as he was about to sink. He held him for some time, and called out to Givan to come to his relief. Givan attempted to reach him, but in vain. At that moment the boat of the Ogdensburg, loaded to the water's edge with rescued passengers, passed and Givan hailed them to save the boy. Mr. Blodgett, first mate of the Atlantic, jumped out and swam to the rope, took the boy off, and returned to the boat with him. He was thus saved.

Erik Thorstad writes in his letter that the press blamed the captain and the owners of the Atlantic for the disaster. The inquiry held into the loss of the ship found that the steering system of both ships was in order, and that the collision was due to a human error, but drew no conclusion as to which ship had caused it. Two theories remain, either that one or both of the pilots had made a careless miscalculation, or that the collision was a result of a deliberate maneuver to injure a rival boat. In a court case brought by the owners of the Atlantic against the owners of Ogdensburg the US Supreme Court in 1856 ruled that both ships were equally to blame for the disaster.

The traffic on the Great Lakes was a lucrative business for the ship owners and speed was a decisive element in the competition to attract more passengers. The fastest ships were powered by steam, and in the quest for speed and new records the boilers often were forced to an extent that affected the safety of the passengers. Several serious accidents involving boilers that were overloaded had occurred earlier that summer and the means of preventing such accidents and safety issues in general were already widely discussed in the press.

Less than two weeks after the loss of Atlantic on Lake Erie, the US Congress passed a bill providing for the licensing and inspection of steamboats and a number of safety regulations. These included regulations as to the pressure in the boilers, as well as the carrying of lifeboats, life preservers and other aids in case of trouble.

There is nothing to indicate that the Atlantic disaster had anything to do with her boilers and Erich Thorstads letter indicates the presence of lifeboats. Atlantic was however very much a part of the competition taking place on the Lakes involving speed, and at the time of her disaster held the record of being the fastest ship between Buffalo and Detroit (16 ½ hours). This might explain some of the criticism facing her owners after the loss.

Atlantic's passenger list was lost when she sunk. We owe the knowledge of the number of Norwegian immigrants aboard, and the names of those who perished to Stephen Olson of Manitowoc, Wisconsin (originally from Valdres) who accompanied the Norwegians as a translator and guide. His list of casualties with names and hometowns was published in the periodical "Skandinaven" on October 27, and in the "Christianiaposten" on Navember 22nd. . 1852. According to this list 3 came from Vang, 36 from Slidre, 23 from Aurdal and 5 from Toten, altogether 67 persons.

The wreck of the Atlantic today rests in 165 feet of water on the Canadian side of the border south of Long Point, Ontario. Since shortly after the disaster the wreck has been a target for salvage operations. The most important cause of this was the Atlantic's safe, which contained approximately $35.000 (in 1852 dollars) of American Express gold. As early as in October 1852, a diver named Green set a new depth record for diving 154 feet down to the wreck of the Atlantic. The old record was 126 feet. The safe was brought to the surface by divers in 1856, which was a feat in itself, since dives down to such depths was seen as impossible prior to the sinking of the Atlantic!

The S/S Atlantic was only four years old when she sank, and known for her luxurious interior. The first class state rooms were said to be decorated with gold gilding, tapestries, and carved rosewood furnishings. These rumors attracted bounty hunters and several attempts were made to retrieve items from the wreck. One of the more exotic of these attempts involved an submersible diving bell. The attempt failed, and the wreck of the submersible now rests on or near the deck of the Atlantic.

The wreck was then forgotten, until its rediscovery in 1984 by a local Canadian diver, who retrieved several hundred artifacts, mainly of historic value. A California based salvation company used the buoy placed to mark the find to explore the site and claim the rights to the wreck. A California court granted this right in 1992. Canadian authorities opposed this ruling and finally won the case, the court finding that the wreck of S/S Atlantic rests in Canadian waters and is abandoned by it's owners. The Ontario Government, who the courts deemed to be the owner of the wreck, has promised that artifacts from the ship will be made accessible to the public.

Part of Erik Torstad's letter:

We left Buffalo on a large steamer, called the "Atlantic", in the evening of the same day - August 12 - at eight o'clock. The total number of passengers was 576, comprising 132 Norwegians, a number of Germans, and the rest Americans.

The accident on Lake Erie did get a lot of intention both in Norway and in America. This is a newspaper announcement from "Christianiaposten" September 7th 1852. It was among the first reports about the accident seen in the Norwegian newspapers, and it says nothing about Norwegians being among the deceased. In the newspaper "Correspondenten" on September 15th, there is a letter from Capt. P. M. Petersen on the Bolivar, stating that none of the Norwegians drowned on Lake Erie was likely to have been traveling with him on the Bolivar, as they would most likely be far gone inland by the time the accident occurred. The letter was dated Quebec Aug. 21st. On September 11th there was a new notice in the "Christianiaposten", telling more details about the accident, and was much the same as the article printed in the Gleason's Pictorial, on September 11, 1852. See the transcription below. The news about the accident caused concern among the families of the emigrants that had left Norway that summer, and on November 22nd the "Christianiaposten" was able to present a list with the names of the deceased. You will find the list further down on this page. As years passed after the accident the numbers and details became more and more dramatic. In Hjalmar R. Holand's book "De Norske Settlementenes historie" printed in 1908, the number of passengers aboard the Atlantic had grown to 830, and the number of drowned passengers to 500. This was not the only exaggeration concerning the accident.

Submitted by Debbie Dahl Cole<

The Norwegian victims of the disaster on Lake Erie:

First name

Patronymic

Farm name

Sex

Status

Origin

Listed as in the church records

Additional

Marit

Stephensdatter

Helle

f

enke

Vang in Valdres

Brækken

widow

Ole

Pedersen

Helle

m

ungkarl

Vang in Valdres

Helle

bachelor

Anders

Østenen

Bøe

m

ungkarl

Vang in Valdres

Bøe

bachelor

Finkel

Olsen

Røvang

m

gaardmand

Slidre in Valdres

Røvang

farmer

Guri

Knudsdatter

Røvang*

f

kone

Slidre in Valdres

Røvang

wife

Marit

Finkelsdatter

Røvang*

f

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Røvang

Gullik

Andersen

m

stedsønn

Slidre in Valdres

Lie

stepson

Barbro

Olsdatter

Røvang

f

pige

Slidre in Valdres

Gudmundsdatter Røvang

servant

Ole

Olsen

Hedeland

m

Slidre in Valdres

Hedalen

Ingeborg

Gulbrandsdatter

Hedeland*

f

kone

Slidre in Valdres

Hedalen*

Gulbrand

Olsen

Hedalen

m

broder av Ole

Slidre in Valdres

Hedalen

brother of Ole

Ingeborg

Olsdatter

Hedalen

f

søster

Slidre in Valdres

Hedalen

sister

Ole

Olsen

Moen

m

Slidre in Valdres

Moen

Johannes

Iversen

Rudi

m

gaardmand

Slidre in Valdres

Alfstad

Traveled with 6 children, 2 or 3 most likely survived.

Marit

Johannesdatter

Rudi*

f

kone

Slidre in Valdres

Alfstad*

Iver

Johannesen

Rudi*

m

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Alfstad*

Ole

Johannesen*

Rudi*

m

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Alfstad*

Anne

Johannesdatter*

Rudi*

f

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Alfstad*

Anne

Torstensdatter

Ulves-Eien

f

pige

Slidre in Valdres

Ulven

servant

Nils

Helgesen

Morstad

m

gaardmand

Slidre in Valdres

Mørstad

farmer

Jarond

Olsdatter

Morstad*

f

kone

Slidre in Valdres

Mørstad*

wife

Ole

Nilsen

Morstad*

m

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Mørstad*

Marit

Nilsdatter*

Morstad*

f

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Mørstad*

Ole

Nilsen*

Morstad*

m

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Mørstad*

This could be Nils, the youngest son according to the church records

Knud

Helgesen

Iølen

m

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Joten*

According to the church records this family did not get away, but atleast Knud must have gone.

Anne

Thomasdatter

Oschovd

f

kone

Slidre in Valdres

Nøbben*

Traveled with her husband Nils

Ole

Nilsen

Oschovd*

m

hennes børn

Slidre in Valdres

Nøbben*

her child

Knud

Larsen

Færdens-Eien

m

barn

Slidre in Valdres

Færden*

Ole

Olsen

Braathovd

m

Slidre in Valdres

Brøthrud

Ragnhild

!!

Braathovd

f

kone

Slidre in Valdres

Brøthrud*

Tostensdatter

Ole

Olsen

Braathovd*

m

børn

Slidre in Valdres

Brøthrud*

Knud

Olsen*

Braathovd*

m

børn

Slidre in Valdres

Brøthrud*

Marit

Olsdatter*

Braathovd*

f

børn

Slidre in Valdres

Brøthrud*

Ragnhild

Olsen!!

Braathovd*

f

børn

Slidre in Valdres

Brøthrud*

Carl

Olsen*

Braathovd*

m

børn

Slidre in Valdres

Not noted in the church records, could be the daughter Kari b. 1847?

Sissel

Olsdatter*

Braathovd*

f

børn

Slidre in Valdres

Not noted in the church records, born on the voyage?

Sigri

Reiersdatter

Majestad

f

enken efter Thorsten Nilsen Majestad som døde i Montreal

Slidre in Valdres

Magistad*

the widow of Tosten Nilsen who drowned in Montreal

Turi

Torstensdatter

Majestad*

f

børn

Slidre in Valdres

Magistad*

Marit

Torstensdatter*

Majestad*

f

børn

Slidre in Valdres

Magistad*

Knud

Olsen

Fuggelhaug

m

Aurdal in Valdres

Fuglehaug

Andrea

Tidemansdatter

Fuggelhaug*

f

kone

Aurdal in Valdres

Fuglehaug

Ingri

Knudsdatter

Fuggelhaug*

f

børn

Aurdal in Valdres

Fuglehaug

Sigri

Knudsdatter*

Fuggelhaug*

f

børn

Aurdal in Valdres

Fuglehaug

Ole

Knudsen

Fuggelhaug*

m

børn

Aurdal in Valdres

Fuglehaug

Bøeren

Olsen

Bøen

m

Aurdal in Valdres

Bøen

Bjørn

Marit

!!

Bøen

f

kone

Aurdal in Valdres

Bøen*

Haldorsdatter

Anne

Bøerensdatter

Bøen*

f

barn

Aurdal in Valdres

Bøen*

One more daughter, Kjersti age 4 was also noted in the church records

Syver

Bøle

m

Aurdal in Valdres

Bøle

Barbro

Bøle

f

kone

Aurdal in Valdres

Bøle*

Sigri

Syversdatter

Bøle*

f

barn

Aurdal in Valdres

Bøle*

Aslak

Dølven

m

Aurdal in Valdres

Mitlien

Kari

Dølven

f

kone

Aurdal in Valdres

Mitlien*

Halstensdatter

Maria

Aslaksdatter

Døvlen*

f

barn

Aurdal in Valdres

Mitlien*

Aslak

Aslaksen

Døvlen*

m

barn

Aurdal in Valdres

Mitlien*

Abraham?

Halsteen

Johannessen

Brakahaugen

m

ungkarl

Aurdal in Valdres

not given

bachelor

Guri

!!

!!

f

en pige

Aurdal in Valdres

not identified

"a girl"

Anne

!!

Setterbraaten

f

en kone

Aurdal in Valdres

Sæterbroten

Kjersti

!!

!!

f

børn

Aurdal in Valdres

Sæterbroten*

Anne

!!

!!

f

børn

Aurdal in Valdres

Aabol

Marit

!!

!!

f

børn

Aurdal in Valdres

Aabol

Maria

!!

!!

f

børn

Aurdal in Valdres

Sæterbroten*

Arne

!!

!!

m

børn

Aurdal in Valdres

Sæterbroten*

Ole

Olsen

m

snedker

Thoten

Pernille

Olsen

f

kone

Thoten

Helene

Olsdatter

f

børn

Thoten

Maria

Olsdatter*

f

børn

Thoten

Olaves Argo

Olsen

m

børn

Thoten

born on the voyage?

Kjersti

Bøen

f

Aurdal

Bøen

This child of the Bøen family was not listed in the newspaper notice.

The official number of Norwegian victims diverges between 67 and 68. In the newspaper list there were listed only 67. Kjersti Bøen could be the missing 68th person on the list, but she could also have died during the transatlantic crossing. An other possibility is that the missing person in the newspaper list was a fourth child of Johannes Iversen Rudi/Alfstad. The information from the church records is from the register of people departing the parish.